Abstract

This essay relates the concepts of organizational resilience to those of social marketing, exposing the commonalities between the fields of study and identifying how both associate to each other. Based on the analysis of the literature on both themes, an assessment of the confluences between resilience and the basic attributes of social marketing was made, in order to identify aspects that articulate such domains of knowledge. The proposal presented here indicates that adaptation and change — of behaviors, ways of proceeding, and attitudes, among others — are responsible for linking the study of resilience to the principles of social marketing, both of which are bound by the need to change behaviors and by the required suitability to certain unexpected situations. Regarding social marketing, a focus on the generation of social welfare was observed, while in the case of organizational resilience, companies focused on the inherent need to change to be competitive in the market, taking advantage of opportunities that may arise from a situation of rupture.

Keywords:

Resilience; Social marketing; Change; Adaptation

Resumo

O presente artigo relaciona os conceitos de resiliência organizacional com os de marketing social, buscando expor os pontos em comum entre tais áreas de estudo e identificando de que forma ambas se associam. Tendo como base a análise da literatura referente a ambos os temas, foi realizada uma avaliação das confluências existentes entre a resiliência e os atributos basilares do marketing social, a fim de identificar aspectos que articulassem tais domínios de conhecimento. A proposição aqui apresentada indica que a adaptação e a mudança - de comportamentos, modos de proceder e atitudes, entre outras - compõem o que aproxima o estudo da resiliência dos princípios subjacentes ao marketing social, sendo ambos vinculados pela necessidade de alterar comportamentos e pela adequação a certas situações inesperadas. No caso do marketing social, um foco na geração de bem-estar social seria observado, enquanto, no caso da resiliência organizacional, o foco das empresas estaria na necessidade inerente de mudar para não serem superadas em seu mercado de atuação, aproveitando oportunidades eventualmente surgidas a partir de uma situação de ruptura.

Palavras-chave:

Resiliência; Marketing social; Mudança; Adaptação

Resumen

En este artículo se relacionan los conceptos de resiliencia organizacional con los de marketing social, tratando de exponer las similitudes entre tales áreas de estudio y de identificar cómo ambas se asocian. Con base en el análisis de la bibliografía sobre ambos temas, se realizó una evaluación de las confluencias entre la resiliencia y los atributos básicos del marketing social, para identificar aspectos que articulasen tales dominios del conocimiento. La propuesta que aquí se presenta indica que la adaptación y el cambio -de comportamientos, formas de conducta y actitudes, entre otros- representan lo que aproxima el estudio de la resiliencia de los principios subyacentes al marketing social, pues ambos están vinculados por la necesidad de alterar comportamientos y por la adecuación requerida a ciertas situaciones inesperadas. En cuanto al marketing social, se observaría un enfoque en la generación de bienestar social, mientras que en el caso de la resiliencia organizacional, las empresas se centrarían en la necesidad inherente de cambiar para no ser superadas en su mercado de actuación, aprovechando las oportunidades que puedan surgir de una situación de ruptura.

Palabras clave:

Resiliencia; Marketing social; Cambio; Adaptación

Introduction

Every organization should seek to make the best use of the resources available to it, regardless of the nature of these. Opportunities are only adequately exploited when managers perceive their market advantages and disadvantages in a comparison with competitors — it is also difficult to moderate the weaknesses existing in an organization when one does not have the necessary skill to perceive that there is a gap between it and its congener.

Some changes in the world business context have brought new challenges and different ways of approaching previously usual situations. The increasingly fierce competition, the globalization process, the access to new technologies, among other aspects, are responsible for an increasingly arduous environment. Confrontation in business often surprises companies that demonstrate they cannot subsist in a reality where competition is the key, which is usually observed in times of crisis or in varied adversities.

This situation can be illustrated with a real example (STARR, NEWFROCK and DELUREY, 2003STARR, R.; NEWFROCK, J.; DELUREY, M. Enterprise resilience: managing risk in the networked economy. Strategy+Business, n. 30, 2003.). At the end of the twentieth century, two companies competing in the telecommunications sector had strong dependence on materials from the same semiconductor factory in the state of New Mexico (USA), for the manufacture of their respective mobile phones. However, because of a fire that occurred in this factory at the beginning of the year 2000, there was a rupture in the value chain. Of course, both companies noticed the problem soon, but their reactions were quite different. In the first company, the person responsible for solving supply problems immediately summoned a team of 30 experts in questions related to the value chain that made contacts in other continents to find a solution that would avoid problems in the near future for the company. In that case, they designed new chips, accelerated projects that favored the expansion of production and made use of the company’s influence in order to get more chips from other suppliers. Meanwhile, the other company, with far fewer fail-safe systems or systems able to solve problems in its supply network, presented a critical shortage of chips, in view of the adequate supply to launch a new product. As a result, the first company raised its market share by 3%, while the second company had a drop of the same magnitude and, shortly thereafter, withdrew from the mobile phone market.

This situation exposes a reality that, increasingly, is perceived in the business environment. Because of various changes in the existing risks — and also their interdependence — the way of proceeding in crisis situations has changed, and is constantly changing. Organizations usually treated risk as a potentially dangerous financial disadvantage, which led them to focus their efforts to protect their portfolios against financial losses (STARR, NEWFROCK and DELUREY, 2003STARR, R.; NEWFROCK, J.; DELUREY, M. Enterprise resilience: managing risk in the networked economy. Strategy+Business, n. 30, 2003.). However, as shown by the first company in the cited case, the fact that it managed to avoid a potentially damaging rupture in its value chain, thus adding a competitive advantage compared to the competing company, shows that organizations can benefit from a systemic understanding of the market, the adaptation of necessary processes and risk management. In this way, greater organizational resilience is obtained, a term (explained later) that relates to an adaptation to a new scope.

Despite the need to obtain resilience in the most varied situations, there is a detail rarely addressed in scientific works. In view of the survival of companies, it must be emphasized that they should not only focus on themselves. Society increasingly influences and is impacted by the practices of all organizations, associations, institutions and entities, so it must have a “voice” perceived and considered by them when defining corporate strategies and goals.

Considering that social marketing is a marketing subject that aims to change behaviors, being based on ideas, values and beliefs (KOTLER and LEE, 2008KOTLER, P.; LEE, N. R. Social marketing: influencing behaviors for good. 3. ed.Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2008.), and that increasingly these are necessary for a more vigorous and developed society, the present article aims to approach the organizational resilience from its foundations, proposing an association between both and recognizing possible existing relations. The relevance of such an approach is due to the fact that, increasingly, companies and organizations have been valuing behaviors aimed at social well-being in the long term as a tool that magnifies the perception of the target public regarding the conduct of companies that are an integral part of a social group. Since both consumers and companies are present in the same society (ZENONE, 2006ZENONE, L. C. Marketing social. São Paulo: Thomson Learning, 2006.), both should have in mind their objectives of profitability and subsistence, in the case of companies, and satisfaction of desires, in the case of consumers, but without ever forgetting the generation of well-being to the reality shared by all.

The present text is organized in a logical and reflective way, with emphasis on interpretation and argumentation (SEVERINO, 2000SEVERINO, A. J. Metodologia do trabalho científico. 21. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2000.). It addresses the fundamental concepts of organizational resilience and confronts them with market aspects, correlating aspects of resilience to a specific area of marketing, notably social marketing, which does not necessarily seek to offer products and services to the market, but to change the behavior of individuals aiming at a better society in the long-term, that is, bringing the generation of social welfare to all its components, included both companies and consumers (KOTLER and KELLER, 2012KOTLER, P.; KELLER, K. L. Administração de marketing. 14. ed. Tradução Sonia M. Yamamoto. São Paulo: Pearson, 2012.). The method involves the evaluation of classic and recent texts about resilience, value and social marketing, in order to identify points of convergence indicated by the authors or perceived in the reading (bibliographical research) of works, such as articles, books and websites. The bibliographical research contemplated these works based on an approach in which the attributes of a theme related to the business reality — resilience — that were connected to another, focused on social aspects — social marketing — were sought, thus focusing on organizational and community attributes.

The main contribution of this article is perceived when, once identified the most outstanding characteristics of social marketing — to change behaviors in order to provide long-term well-being —, we can notice a relationship with resilience attributes — especially adaptation and response to changes, as shown below.

Organizational resilience

The word resilience comes from the Latin word resilio, which means returning to a previous state. The term is used in several areas of knowledge, such as engineering and physics, indicating the capacity of a body to return to its original state after great pressure exerted on its mass (YUNES, 2003YUNES, M. A. M. Psicologia positiva e resiliência: o foco no indivíduo e na família. Psicologia em Estudo, n. 8, p. 75-84, 2003.). In translating the term into the human sciences, its meaning was defined as the ability of an individual — or a group of them —, even in an adverse environment, to construct or rebuild positively before of mishaps or setbacks (BARLACH, LIMONGI-FRANCE and MALVEZZI, 2008BARLACH, L.; LIMONGI-FRANÇA, A. C.; MALVEZZI, S. O conceito de resiliência aplicado ao trabalho nas organizações. Revista Interamericana de Psicología, v. 42, n. 1, p. 101-112, 2008.). In the field of administration, resilience would be a term that would denote an interaction between the environment and the subject, or system, embedded in it, thus demarcating two different types of resilience: of people in the organizational environment and of the organizations themselves (IRIGARAY, GOLDSCHMIDT, QUEIROZ et al., 2016IRIGARAY, H. A. R. et al. Resiliência, orientação sexual e ambiente de trabalho: uma conversa possível?. In: XLENANPAD2016. Anais…Costa do Sauípe, BA, set. 2016.).

In an organizational context, the term resilience refers to an ability to dynamically reinvent business models and strategies as the circumstances or context change (HAMEL and VÄLIKANGAS, 2003HAMEL, G.; VÄLIKANGAS, L. The quest for resilience. Harvard Business Review, p. 1-12, set. 2003.). At the core, in this case, would be the anticipation of trends capable of causing permanent damage to the main business of an organization, which would be able to prevent problems that, once they arise, would not have simple or possible solutions, and to perceive the need for change before it becomes unquestionable because of the situation that has arisen.

Organizational resilience is defined as:

The organizational ability to deal with recovery, rapid adaptation, and effective change of disruptive events (such as changes produced by real innovation) into a virtuous circle, rapidly reaching a productive state for growth and development at a more complex organizational level. (VASCONCELOS, CYRINO, D’OLIVEIRA et al., 2015VASCONCELOS, I. F. F. G. et al. Resiliência organizacional e inovação sustentável: um estudo sobre o modelo de gestão de pessoas de uma empresa brasileira de energia. Cad. EBAPE.BR, v. 13, n. 4, p. 912-929, out./dez. 2015., p. 914)

It can be observed that resilient institutions are not satisfied with the perpetuity of eventual situations with which certain players have already become accustomed to — these institutions have as a guide a behavior of re-adaptation, of continuous rebuilding of conduits and innovation in their procedures.

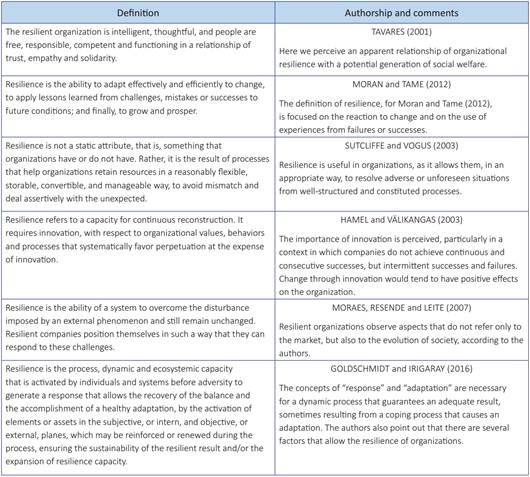

Chart 1 shows the understanding of organizational resilience for some authors, where it is possible to perceive some convergence in the definitions.

Some authors discuss resilience in terms of identifying whether it would be the case to understand an organization that seeks to remain profitable “despite” adversities — when the characteristics prior to the observed conflict are preserved through some adaptation — or “through” them — which occurs when a risk condition is seen as an opportunity to overcome its own limits, in a situation of overcoming that favors the strengthening of the organization’s identity (TABOADA, LEGAL and MACHADO, 2006TABOADA, N. G.; LEGAL, E. J.; MACHADO, N. Resiliência: em busca de um conceito. Rev. Bras. Crescimento Desenvolv. Hum., v. 16, n. 3, p. 104-113, 2006.).

In broad terms, resilient entities have three characteristics in common (COUTU, 2002COUTU, D. L. How resilience works. Harvard Business Review, v. 80, n. 5, p. 46-55, maio2002.): they accept, in a rational way, a reality that is more intricate; they find meaning in times of need or difficulties; and manage to find solutions with whatever is at hand, through inventiveness, creativity and even improvisation.

Strictly speaking, there are four challenges to be overcome by organizations that intend to become resilient: cognitive, strategic, political and ideological (HAMEL and VÄLIKANGAS, 2003HAMEL, G.; VÄLIKANGAS, L. The quest for resilience. Harvard Business Review, p. 1-12, set. 2003.). In the case of cognitive challenge, the organization must have a deep awareness of what has been changing in the reality in which it operates and thus evaluate how these changes affect its reality and feasible market success. The strategic challenge indicates that resilience requires awareness, that is, an efficient ability to create new attractive alternatives to strategies that are either innocuous or old. The political challenge, which indicates that companies must be able to escape from varied situations through talent and capital, warns that it is necessary to shift funds towards products at the end of their life cycle to those in growth, with better prospects and without aiming at extravagances. And the ideological challenge is vital to the future of the organization, since it is based on the perception that only the optimization of business models that may gradually become irrelevant does not guarantee the subsistence of institutions. This requires timely and continuous renewals — rather than episodic ones — as well as the need for companies to conserve and share among their members a belief that spreads beyond operational excellence.

It is noticeable how difficult is for an organization to become resilient based on the challenges presented. Aspects such as innovation and renewal, often remembered, are not enough for organizational resilience to occur properly in a given market. The perception that organizations can become resilient is found in varied fields such as engineering, psychology, ecology, and others, generally identifying a resistance of the institutions and individuals composing them to withstand adversity in general — which would include disruptions, dismemberment, instability and change — with greater vigor than conventional. The idea of resilience is further reinforced in the literature through comparisons between firms that have survived successfully after events considered abrupt or extreme — such as terrorist attacks, stock market crashes, severe political and economic crises and similar circumstances (LINNENLUECKE and GRIFFITHS, 2013LINNENLUECKE, M. K.; GRIFFITHS, A. The 2009 Victorian bushfires: a multilevel perspective on organizational risk and resilience. Organization & Environment, v. 26, n. 4, p. 386-411, 2013.). Such notions are commonly emphasized in order to prove that resilient companies have the capacity to recover, or even to strengthen, after adverse events, whereas others — non-resilient ones — would tend to face difficulties or even bankrupt, as a consequence of the problems faced.

Considering the importance of resilience to organizations, it becomes prominent to identify how capacity for resilience is developed. Lengnick et al. (apud ALBUQUERQUE and PEDRON, 2014ALBUQUERQUE, R. A. F.; PEDRON, C. D. Resiliência organizacional: um ensaio teórico. In: IIISINGEP; II S2IS. Anais…São Paulo, 2014.) show that three dimensions are relevant in this recognition: cognitive, behavioral and contextual resiliency.

Cognitive resilience refers to the ability and efficiency with which an organization faces changes in its daily activities, evaluates available alternatives according to the context experienced, appreciates new conjunctures and generates responses to disruptive stimuli suffered. Behavioral resilience, on the other side, refers to the ways in which an organization, under a situation of uncertainty and routine discontinuity, acquires knowledge about such a situation, implements new forms of action and makes use of its resources in conditions of uncertainty. In this dimension, one must understand the organization’s specific procedures and corporate rituals in order to value the decisions made. In turn, contextual resilience is responsible for providing resources that favor the evolution of the other two dimensions cited. This dimension of resilience, recognizing a situation of disruption and insecurity, focuses the resources needed for immediate action — including the links between civil servants and other human resources — that are capable of avoiding potentially harmful or potentially damaging consequences for the organization in the long term.

In this paper, it is worth mentioning Barlach’s (2005BARLACH, L. O que é resiliência humana? Uma contribuição para a construção do conceito. Dissertação (Mestrado), Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2005. 119 p.) position, in which organizational resilience is a construction of creative solutions to adversities arising not only in working conditions but also in today’s society, which would require a renewal of competencies to face changes aiming at improving themselves and society when adverse conditions arise. As will be discussed later, such characteristics show an affinity with the conceptual basis of social marketing, in which changes in behaviors, values, beliefs and attitudes can be demanded in order to construct a more beneficial reality for all.

Resilience, changes and values

The concept of resilience is very dynamic and dependent on the scenario evaluated. The connection between organizational resilience and change, in its broadest sense, is easily discernible. Once something is presented differently from the conventional form, some action, or conduct, will be necessary — both to restore some damage and to take advantage of the new market context in order to better position the organization. Organizational changes usually occur after some kind of failures or shortcomings.

Changes can be episodic or continuous (WEICK and QUINN, 1999WEICK, K. E.; QUINN, R. E. Organizational change and development. Annual Review of Psychology, n. 50, p. 361-386, 1999.). The episodic indicates infrequent, discontinuous, and purposeful organizational changes that would occur in situations in which organizations show a move away from a condition of equilibrium. By perceiving as a result a gradual misalignment between the inertial corporate structure and the demands of the external environment, occurs what is known as divergence. Such a form of change is called episodic because it usually occurs at specific times, in which external events bring about ruptures between the usual situation and that arising from an external stimulus. The emphasis in this case should be on a short-term adaptation, so that the new conditions presented do not cause long-term damage.

Continuous change, as opposed to episodic, has a local perspective, while episodic change is global. In addition, the emphasis of continuous change is on a long-term adaptation (WEICK and QUINN, 1999WEICK, K. E.; QUINN, R. E. Organizational change and development. Annual Review of Psychology, n. 50, p. 361-386, 1999.). Its most striking feature is the existence of constant continuous adjustments, occurring jointly between the business units, which can cause portentous changes in the organization as a whole. Thus, the idea of interdependence is assumed, without which there would be convergence of actions focused on smaller strategic units, dispersed, which would only be important as areas of innovation in the organization, which could be adequate in future environments.

Regardless of the essence of the change, there must be a modification of approach in organizations for resilience to arise. Such an approach should no longer be reactive, but proactive, since cadence and the pace of organizational changes have been occurring more rapidly, requiring greater skill and speed of managers. These should show adaptive capacity (SANTOS and KATO, 2014SANTOS, C. B.; KATO, H. T. Ambiente e resiliência organizacional: possíveis relações sob a perspectiva das capacidades dinâmicas. Desafio Online, Campo Grande, v. 2, n. 1, p. 564-579, jan./abr. 2014.), as well as leadership to bring with them those who, in fact, have the predisposition to mitigate crises once identified. The faster the response to an adverse scenario in the perception of the stakeholders of an organization, the greater the value perceived by them and, consequently, the greater the charisma and affection that the organization will tend to receive for its prompt response.

Value is defined as the relationship between benefits and costs (KOTLER and KELLER, 2012KOTLER, P.; KELLER, K. L. Administração de marketing. 14. ed. Tradução Sonia M. Yamamoto. São Paulo: Pearson, 2012.). The value would thus be broadly understood as a general assessment by the consumer as to the usefulness of a product (or service), based on the perception of what is received compared to what is delivered in that process of exchange (ZEITHAML, 1988ZEITHAML, V. A. Consumer perception of price, quality and value: a means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing, v. 52, n. 3, p. 2-22, jul. 1988.). Thus, in order to assess the value of a corporation from the perspective of its stakeholders, it would be necessary to measure the benefits delivered by it, compared to the costs — financial and non-financial — that must be incurred in order to obtain such benefits.

In the case of an organization that presents resilience, this feature alone would already indicate a benefit, and others should still be sought in order to raise the value of the organization. However, the costs incurred to achieve benefits in general are not only monetary or financial; They comprise any effort or sacrifice in terms of psychological, physical and temporal energy, among others, related to risk in general (KOTLER and KELLER, 2012KOTLER, P.; KELLER, K. L. Administração de marketing. 14. ed. Tradução Sonia M. Yamamoto. São Paulo: Pearson, 2012.), as can be seen in Figure 1. Psychological efforts refer to uncertainties arising from an acquired product or a service rendered. For example, a consumer who undergoes a plastic surgery will perceive a sense of uncertainty as to the final result. In terms of physical energy, it refers to some physical effort to be taken when acquiring something, as in the case of a patient who goes to the dentist and should keep his mouth open for a long time in order to perform some procedure. And the temporal efforts are those related to the time spent, when one should wait in a queue for care, for example.

What can be observed is that the benefits perceived by consumers and other stakeholders are practical and emotional, and the existing sacrifices involve the expenditure of financial resources, energy and others, whose intensity depends on the person measuring the value received, that is, comparing what is positive and negative about what is received. Clients will act and make decisions based on an expectation of value, and will favor the organization which presents them with the greatest value in comparison to competitors. This shows that perceived value is a positive function of what is received, and a negative function of which is sacrificed for the receipt to take place (IKEDA and VELUDO-DE-OLIVEIRA, 2005IKEDA, A. A.; VELUDO-DE-OLIVEIRA, T. M. O conceito de valor para o cliente: definições e implicações gerenciais em marketing. REAd, ed. 44, v. 11, n. 2, p. 1-22, 2005.).

Value creation happens, from the corporate point of view, when total returns exceed the values necessary for the continuation of the organization’s operational activities (BAKER, 2003BAKER, M. J. The marketing book. 5. ed. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann, 2003.). Therefore, such reference must be in the planning of the organizations when carrying out some evaluation of possible future investments. It must also be considered that, in order to reap favorable reactions from society, companies have increasingly been concerned and acting to provide well-being to consumers.

Social marketing and resilience

It is common, when evaluating the traditional concept of marketing, to relate that term to advertising, disclosure and sale of products. Although the concept of marketing is actually much broader, there are variations on this field of study that deserve to be addressed when analyzing the industry and markets in which resilient organizations appear as protagonists.

Marketing is defined as “a social process through which individuals and groups obtain what they need and desire through the creation, supply and free exchange of valuable products” (KOTLER and KELLER, 2012KOTLER, P.; KELLER, K. L. Administração de marketing. 14. ed. Tradução Sonia M. Yamamoto. São Paulo: Pearson, 2012., p.4), and marketing management is defined as “the art and science of selecting target markets and capturing, maintaining and retaining customers through the creation, delivery, and communication of superior value to the customer” (KOTLER and KELLER, 2012KOTLER, P.; KELLER, K. L. Administração de marketing. 14. ed. Tradução Sonia M. Yamamoto. São Paulo: Pearson, 2012., p. 3). So, there is a strong convergence of market-related aspects. Being market composed of sets of consumers, surely they will seek the greatest possible value when facing a transaction of any nature. And a way to add value to what is offered to the market is through the creation of well-being and prosperity.

Social marketing does not have a categorical definition (DANN, 2010DANN, S. Redefining social marketing with contemporary commercial marketing definitions. Journal of Business Research, v. 63, p. 147-153, 2010.), being understood as a marketing subject that focuses not on the offer of products and services, but on the change of behaviors, beliefs, attitudes, values, practices and the like. According to Zenone (2006ZENONE, L. C. Marketing social. São Paulo: Thomson Learning, 2006.), the use of the term “social marketing” is adequate in a situation in which a company or institution uses social procedures compatible with marketing, aiming to bring benefits to the whole society. The author also focuses on adapting to a new market reality — an adaptation that is similar to that of resilience — as in Andreasen’s (1994ANDREASEN, A. R. Social marketing: its definition and domain. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, v. 13, n. 1, p. 108-114, 1994., p. 110) definition, presented in Chart 2. It is also relevant to observe the involvement of social marketing with “changes in attitudes, beliefs and behaviors of individuals or organizations” in order to obtain a social benefit (RANGUN and KARIM, 1991RANGUN, V. K.; KARIM, S. Teaching note: focusing the concept of social marketing. Cambridge: Harvard Business School, 1991., p.3). It is common to use expressions such as “change”, “transformation” and “interchange” to refer to the core of social marketing. In Chart 2, some definitions are shown that prove such perception.

Two items should be noted regarding social marketing programs: (i) there is a methodical use of trading — given that marketing refers to markets themselves — in the form of change planning; and (ii) social marketing is understood as an influencer of society, in the sense that it has persuasiveness through its campaigns to change behaviors, beliefs, practices, behaviors and values (DANN, 2010DANN, S. Redefining social marketing with contemporary commercial marketing definitions. Journal of Business Research, v. 63, p. 147-153, 2010.). The behavioral change would be achieved through the creation, communication, delivery and exchange of competitive social marketing offers, which would be capable of provoking voluntary change of the target audience (ANDREASEN, 1994ANDREASEN, A. R. Social marketing: its definition and domain. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, v. 13, n. 1, p. 108-114, 1994.), thus generating advantages for the beneficiaries of the social marketing campaign, in addition to the partners of the organization that promotes the campaign and society in general (FRENCH and RUSSELL-BENNETT, 2015FRENCH, J.; RUSSELL-BENNETT, R. A hierarchical model of social marketing. Journal of Social Marketing, v. 5, n. 2, p. 139-159, 2015.).

It should be noted that there are perceptible differences between traditional marketing and social marketing. In traditional marketing, companies relate to consumers in order to satisfy their desires and to profit, without major concerns about changes that may occur or impact the environment surrounding the company, while in social marketing there is a focus on society, since it encompasses both companies and consumers, which legitimizes the occurrence of social campaigns with the purpose of generating beneficial changes to the components of society (KAMLOT, 2012KAMLOT, D. Interferência do Estado na sociedade: uma visão de marketing social. Revista da ESPM, v. 19, p. 78-83, 2012.) and also to the organizations and their stakeholders (DONOVAN and HENLEY, 2010DONOVAN, R.; HENLEY, N. Principles and practice of social marketing: an international perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.).

Here, before the exposed content, it is shown the proposition of the present article. Changes, especially voluntary ones, support an observed relationship between organizational resilience and social marketing. Considering that resilient organizations must be alert to changes and eventual adaptations to new contexts to obtain positive results, and that social marketing advocates that behavioral changes must occur in order to generate a welfare for society as a whole, it is sustained the relevance of adaptive capacity (SUTCLIFFE and VOGUS, 2003SUTCLIFFE, K.; VOGUS, T. Organizing for resilience. In: CAMERON, K. S.; DUTTON, J. E.; QUINN, R. E. Q. (Ed.). Positive organizational scholarship: foundations of a new discipline. São Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 2003.; MORAN and TAME, 2012MORAN, B.; TAME, P. Organizational resilience: uniting leadership and enhancing sustainability. Sustainability: The Journal of Record, v. 5, n. 4, p. 233-237, 2012.; SANTOS and KATO, 2014SANTOS, C. B.; KATO, H. T. Ambiente e resiliência organizacional: possíveis relações sob a perspectiva das capacidades dinâmicas. Desafio Online, Campo Grande, v. 2, n. 1, p. 564-579, jan./abr. 2014.; GOLDSCHMIDT and IRIGARAY, 2016IRIGARAY, H. A. R. et al. Resiliência, orientação sexual e ambiente de trabalho: uma conversa possível?. In: XLENANPAD2016. Anais…Costa do Sauípe, BA, set. 2016.), because it is an element that presents itself as an aggregator between resilience and social marketing, since in resilience this capacity allows the use of opportunities, and in social marketing it is necessary for a change in behavior in search of improvements to society. In both cases, something salubrious would be achieved because of the adaptation or the actual change. Social marketing and resilience would be linked by the need to adapt to unusual, unforeseeable situations or in need of urgent intervention.

Based on the resilience characteristics presented in the literature (that this field of study must take into account not only the change, but the resolution of adverse or unforeseen situations and the adaptation to new market characteristics, besides attributes that are directed to the evolution of society, rather than just the market) and observing the theoretical foundations of social marketing (which indicate that transformations are necessary to direct the organization to generate social welfare in the long term, through adaptations to induce change, influencing behaviors and attitudes, seeking to evolve voluntarily by the knowledge of needs and obstacles in society, as well as demand planning and action), it is possible to note the relationship between social marketing and resilience in varied contexts, however related to adaptation — management, processes, development, among others —, provided that the change is managed respecting mutual influences between the areas under study, as shown in Figure 2.

Social marketing has a more perceptible relationship with episodic change, since infrequent and purposeful changes that would occur in situations where the ideal condition — of well-being generated to the society — was not observed, would lead to a deviation from the equilibrium condition. In this case, the divergence would occur due to the fact that the social welfare sought was not reached, but that there were conditions for the behavior change of members of society to occur through a short-term adaptation, in order to ensure that the new conditions presented favor as many individuals as possible.

Thus, when evaluating the precepts of organizational resilience and social marketing, some intersections can be highlighted in the present proposition. To do so, it is recommended to return to the definition of resilience presented by Vasconcelos, Cyrino, D’Oliveira et al. (2015VASCONCELOS, I. F. F. G. et al. Resiliência organizacional e inovação sustentável: um estudo sobre o modelo de gestão de pessoas de uma empresa brasileira de energia. Cad. EBAPE.BR, v. 13, n. 4, p. 912-929, out./dez. 2015., p. 914). Considering this definition and making an analogy about the changes in society, intrinsic to the conceptualization of social marketing, it is proposed here that: (i) as organizational resilience refers to changes in the conduct of the members of the organization itself, aiming at an adaptation to better respond to the environment that encompasses it, in social marketing change and adaptation also stand out, referring to the change in behavior of the members of society, aiming at an adaptation that brings benefits to society as a whole; (ii) when dealing with resilience, it is relevant to observe the potential disruptive events that may cause future problems to the organization. This requires procedures that facilitate the adaptation of corporate members to the new reality that arises; in social marketing, the players move from a situation considered disruptive to society — such as harmful behavior, including disrespect for rules of coexistence, disobedience to safety standards, among others — to transform behavior and adapt it to a reality in which well-being is the key; and (iii) the development of the resilient organization is due to improvements that have taken place in organizational terms, based on modifications that impact the daily life of the company and eventually generate a positive impact on society in general. In the case of the reality of social marketing, it is observed that the society develops from noble social and marketing practices divulged in the so-called social campaigns, destined to the change of behaviors, ideas, values, beliefs and attitudes.

The scheme presented in Figure 2, based on Dann (2010DANN, S. Redefining social marketing with contemporary commercial marketing definitions. Journal of Business Research, v. 63, p. 147-153, 2010.), elicits the congregation of social marketing values and their relationship with organizational resilience.

Figure 2 shows a schema proposed from the literature on social marketing and resilience where the situations in which resilience is perceived are presented, as well as their respective focuses and the indication of the mechanisms related to each set of activities. From the initial mechanism indicated, one of four groups of activities is reached: Marketing — whose affinity of ideas with social marketing is based on the definition of the Chartered Institute of Marketers (2005 apud DANN, 2010DANN, S. Redefining social marketing with contemporary commercial marketing definitions. Journal of Business Research, v. 63, p. 147-153, 2010.) —, Behavior — from the definition of the British National Social Marketing Center (2006, apud DANN, 2010DANN, S. Redefining social marketing with contemporary commercial marketing definitions. Journal of Business Research, v. 63, p. 147-153, 2010.), — Voluntariness — based on the definition of the American Marketing Association (AMA) (2008), or Benefits — based on the definition of Kotler and Lee (2008KOTLER, P.; LEE, N. R. Social marketing: influencing behaviors for good. 3. ed.Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2008.). Citations to resilience, in each case, show a focus on some of the specificities mentioned above, which may refer to processes, changes or organizational development. In any case, resilience is observed in a context where benefits, the occurrence of transformations, the advent of adaptations or the improvement of activities and institutions are observed. Once again, the relationship between social marketing and resilience is observed from the adaptations and changes that occurred.

The construction of the benefit to society is focused on the return achieved above the cost of adoption — something relative, since the perception of costs varies from individual to individual, from organization to organization and from society to society. The scheme depicted in Figure 2, although based on current literature definitions and general knowledge about resilience and social marketing, can be understood as a theoretical orientation from which new approaches can be conceived, considering that exists, within the marketing topics, specific disciplines that relate to concepts of extreme relevance in corporate terms, as is the case of resilience and its connection with social marketing.

Final considerations

This article has addressed the main concepts related to organizational resilience and social marketing, two areas where there is little published content with some connection between the two.

The essence of what has been evaluated relates to adaptation, changes, social welfare, resolution of adverse or unforeseen situations, new market characteristics and changes in behavior. Although they are recurrent themes in the literature on organizational resilience and social marketing, no attempt has been identified to bring them together, seeking something shared by researchers from both areas. There are few studies and researches currently available that deal with such subjects together, although their precepts are exposed in quite varied works, but in which such topics are analyzed without relating to one another.

The analysis of aspects of resilience encompasses not only recovery from adverse situations, but also effective adaptation and change arising from disruptive events, i.e., a change from a new juncture. In the case of social marketing, it was observed that the change in behaviors, attitudes, beliefs and values occurs in response to a new context, or to an eventual noxious situation that is perceived and demands a reaction aimed at generating well-being for society as a whole. In both cases, the emphasis is on adaptation and change.

Competition remains in the most varied markets, and reality must be considered in the planning of organizations, aiming not only for their profitability, but also for the well-being and prosperity of the society of which both corporations and consumers are part. As resilience can be understood as “the ability of a system to overcome the disturbance imposed by an external phenomenon and yet remain unchanged” (MORAES, RESENDE and LEITE, 2007MORAES, S. C. S; RESENDE, L. M.; LEITE, M. L. G. Resiliência organizacional: atributo de competitividade na era da incerteza. In: CONGRESSO INTERNACIONAL DE ADMINISTRAÇÃO - GESTÃO ESTRATÉGICA PARA O DESENVOLVIMENTO SUSTENTÁVEL. Anais… Ponta Grossa, PR, 2007.), it is necessary for companies, to become resilient, to observe aspects which relate not only to the market but also to the evolution of society.

At this point, we must observe the social marketing precepts that are consistent with the need for resilience by organizations. While the term “change” is common for resilient companies, for those who adhere to the fundamentals of social marketing, change occurs in behavior, and can be extended to ideas, attitudes, beliefs and values, among other features. Just as resilient companies understand change as something necessary, related to development itself, when the focus is on the social issue, such companies must pay attention to the fact that, because they are part of society, they must collaborate for its development and for the expansion of robustness and vigor intrinsic to the observed reality.

The proposition presented in this article, that social marketing and resilience would be bound by the need to change behaviors or by adapting to certain unexpected situations that require action or rapid interference, represents a new perception, still little explored, that focuses on situations in which organizations and society would relate, taking adaptation as a common point, both for taking advantage of opportunities and for a transformation in procedures.

As presented in the literature on the subjects studied, there are several mechanisms composing the nuclei that define social marketing. The perception of where resilience is observed is based on the consideration that the existing processes — and perhaps subject to change —, the necessary changes in specific situations and the organizational development essential to the evolution of the corporations are what directs the resilience from an approach whose core lies in the definition of social marketing and in the use of well-performed and timely adaptation.

Of the four groups of activities identified as related to the principles of social marketing, it should be emphasized the existing communication with aspects of organizational resilience. In the case of the Marketing group, where the focus is on processes, these should be adapted — based on the precepts of social marketing — to commercial marketing activities, taking into account characteristics of profitability, management and the consumer him/herself. As for Behavior, whose core is in changes, it is important to note that these can be given in a definitive or provisional way, from the creation of new ways of acting, including the conceiving of new concepts, new goals and new working methods. Voluntariness clarifies that organizational or social change must be achieved through non-coercive means, by focusing on activities that assist stakeholders and the society in which the organization exists to add value to the activities carried out. Finally, the Benefits are understood as a return to the corporation for the investments made by it, which exceed the financial and non-financial costs of the activity performed. The benefits derived are perceived as advantageous to the target market of the organization and to the community as a whole.

In short, marketing and resilience issues must be considered in order to achieve behavioral variations through voluntary changes in organizations, markets and society. The benefits that arise will be responsible for raising the perception of value by all those affected, thus contributing to the assimilation that resilient entities tend to have better results and to the understanding that organizations which, with the change of behavior, are also genuinely concerned about social improvements, will be more valued. The proposition that adaptation and change — of behaviors, procedures and attitudes, among others — connect the principles of social marketing to resilience, both of which are bound by the need to change behaviors and by adequacy to certain unexpected situations, is noted and expected when organizational changes as a result of market or macro-environmental changes lead to a new environment in which social well-being also happens.

The present paper does not seek to be understood as a definitive text on resilience or social marketing, but as a study that serves as a basis for eventual specific needs that relate the two fields of study. Since social marketing is an area that has not yet been explored, particularly in Brazil, and since the study of organizational resilience is a field with enormous potential to be explored in future studies, it is recommended to evaluate resilience dimensions related to other specific areas, such as retail marketing and service marketing.

Referências

- ALBUQUERQUE, R. A. F.; PEDRON, C. D. Resiliência organizacional: um ensaio teórico. In: IIISINGEP; II S2IS. Anais…São Paulo, 2014.

- AMERICAN MARKETING ASSOCIATION (AMA). Definition of marketing. Jul. 2013. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://www.ama.org/AboutAMA/Pages/Definition-of-Marketing.aspx >. Acesso em: 10 mar. 2016.

» https://www.ama.org/AboutAMA/Pages/Definition-of-Marketing.aspx - ANDREASEN, A. R. Social marketing: its definition and domain. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, v. 13, n. 1, p. 108-114, 1994.

- BAKER, M. J. The marketing book. 5. ed. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann, 2003.

- BARLACH, L. O que é resiliência humana? Uma contribuição para a construção do conceito. Dissertação (Mestrado), Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2005. 119 p.

- BARLACH, L.; LIMONGI-FRANÇA, A. C.; MALVEZZI, S. O conceito de resiliência aplicado ao trabalho nas organizações. Revista Interamericana de Psicología, v. 42, n. 1, p. 101-112, 2008.

- COUTU, D. L. How resilience works. Harvard Business Review, v. 80, n. 5, p. 46-55, maio2002.

- DANN, S. Redefining social marketing with contemporary commercial marketing definitions. Journal of Business Research, v. 63, p. 147-153, 2010.

- DONOVAN, R.; HENLEY, N. Principles and practice of social marketing: an international perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- ESTEBAN, A. Principios de marketing. Madri: Esic, 1997.

- FRENCH, J.; RUSSELL-BENNETT, R. A hierarchical model of social marketing. Journal of Social Marketing, v. 5, n. 2, p. 139-159, 2015.

- GOLDSCHMIDT, C. C.; IRIGARAY, H. A. R. Resiliência: (des)construindo o constructo sob a ótica dos gestores. In: IX ENEO2016. Anais…Belo Horizonte, maio2016.

- HAMEL, G.; VÄLIKANGAS, L. The quest for resilience. Harvard Business Review, p. 1-12, set. 2003.

- IKEDA, A. A.; VELUDO-DE-OLIVEIRA, T. M. O conceito de valor para o cliente: definições e implicações gerenciais em marketing. REAd, ed. 44, v. 11, n. 2, p. 1-22, 2005.

- IRIGARAY, H. A. R. et al. Resiliência, orientação sexual e ambiente de trabalho: uma conversa possível?. In: XLENANPAD2016. Anais…Costa do Sauípe, BA, set. 2016.

- KAMLOT, D. Interferência do Estado na sociedade: uma visão de marketing social. Revista da ESPM, v. 19, p. 78-83, 2012.

- KOTLER, P.; KELLER, K. L. Administração de marketing. 14. ed. Tradução Sonia M. Yamamoto. São Paulo: Pearson, 2012.

- KOTLER, P.; LEE, N. R. Social marketing: influencing behaviors for good. 3. ed.Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2008.

- KOTLER, P.; ROBERTO, E. Marketing social: estratégias para alterar o comportamento público. Rio de Janeiro: Campus, 1992.

- KOTLER, P.; ZALTMAN, G. Social marketing: an approach to planned social change. Journal of Marketing, v. 35, n. 3, p. 3-12, jul. 1971.

- LEAL, A. Gestión del marketing social. Madri: McGraw-Hill, 2000.

- LINNENLUECKE, M. K.; GRIFFITHS, A. The 2009 Victorian bushfires: a multilevel perspective on organizational risk and resilience. Organization & Environment, v. 26, n. 4, p. 386-411, 2013.

- LONGSTAFF, P. H. et al. Building resilient communities: a preliminary framework for assessment. Homeland Security Affairs, v. 6, n. 3, p. 1-23, 2010.

- MORAES, S. C. S; RESENDE, L. M.; LEITE, M. L. G. Resiliência organizacional: atributo de competitividade na era da incerteza. In: CONGRESSO INTERNACIONAL DE ADMINISTRAÇÃO - GESTÃO ESTRATÉGICA PARA O DESENVOLVIMENTO SUSTENTÁVEL. Anais… Ponta Grossa, PR, 2007.

- MORAN, B.; TAME, P. Organizational resilience: uniting leadership and enhancing sustainability. Sustainability: The Journal of Record, v. 5, n. 4, p. 233-237, 2012.

- RANGUN, V. K.; KARIM, S. Teaching note: focusing the concept of social marketing. Cambridge: Harvard Business School, 1991.

- SANTOS, C. B.; KATO, H. T. Ambiente e resiliência organizacional: possíveis relações sob a perspectiva das capacidades dinâmicas. Desafio Online, Campo Grande, v. 2, n. 1, p. 564-579, jan./abr. 2014.

- SEVERINO, A. J. Metodologia do trabalho científico. 21. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2000.

- SILVA, E. C.; MINCIOTTI, S. A. Marketing ortodoxo, societal e social: as diferentes relações de troca com a sociedade. Revista Brasileira de Gestão de Negócios, v. 7, n. 17, p. 15-22, 2005.

- STARR, R.; NEWFROCK, J.; DELUREY, M. Enterprise resilience: managing risk in the networked economy. Strategy+Business, n. 30, 2003.

- SUTCLIFFE, K.; VOGUS, T. Organizing for resilience. In: CAMERON, K. S.; DUTTON, J. E.; QUINN, R. E. Q. (Ed.). Positive organizational scholarship: foundations of a new discipline. São Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 2003.

- TABOADA, N. G.; LEGAL, E. J.; MACHADO, N. Resiliência: em busca de um conceito. Rev. Bras. Crescimento Desenvolv. Hum., v. 16, n. 3, p. 104-113, 2006.

- TAVARES, J. A. Resiliência na sociedade emergente. In: TAVARES, J. A. (Org.). Resiliência e educação. São Paulo: Cortez, 2001. 43-76 p.

- VASCONCELOS, I. F. F. G. et al. Resiliência organizacional e inovação sustentável: um estudo sobre o modelo de gestão de pessoas de uma empresa brasileira de energia. Cad. EBAPE.BR, v. 13, n. 4, p. 912-929, out./dez. 2015.

- WEICK, K. E.; QUINN, R. E. Organizational change and development. Annual Review of Psychology, n. 50, p. 361-386, 1999.

- YUNES, M. A. M. Psicologia positiva e resiliência: o foco no indivíduo e na família. Psicologia em Estudo, n. 8, p. 75-84, 2003.

- ZEITHAML, V. A. Consumer perception of price, quality and value: a means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing, v. 52, n. 3, p. 2-22, jul. 1988.

- ZENONE, L. C. Marketing social. São Paulo: Thomson Learning, 2006.

-

5

Image source: Pixabay. Available at: <https://pixabay.com/pt/equipe-grupo-silhuetas-homem-84827/>. Accessed on June 25, 2017.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

Sept 2017

History

-

Received

29 Mar 2016 -

Accepted

01 June 2017

Sources:

Sources:  Source:

Source:

Source: Adapted from

Source: Adapted from